November

Eid عيد الفطر

The sharpened tip of the butcher’s knife rested on Isaac’s chest. Its blade would soon split his skin, slice between ribs, and dismantle his heart. As it plunged downward the knife would also puncture Isaac’s left lung and continue tearing through muscle and sinew before exiting the back of the body and grinding to a halt against the same stone slab he was tied to.

Earlier that day, as he prepared for the sacrifice, Abraham and his wife, Hajar, had been tempted by the Devil, who said he could dissolve the deal Abraham had made with God. If Abraham and Hajar simply submitted to Satan, their only son’s life would be spared.

But they didn’t submit. Instead, Hajar and Isaac had thrown rocks and stones at the Devil until they eventually drove him away.

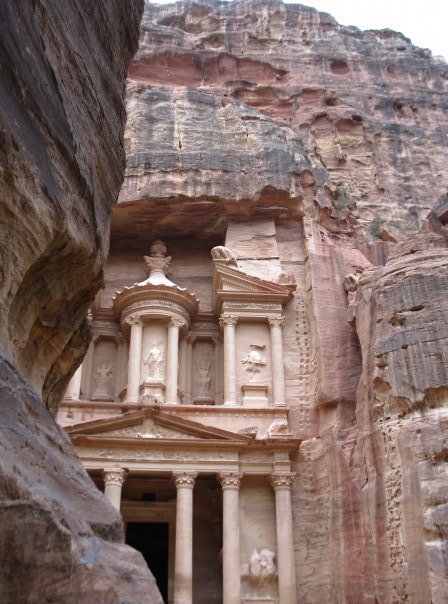

The Prophet Abraham and his family came from the land of Canaan where they’d lived happily for many years. One day God had asked Abraham to move his family to the valley of Mecca, an uninhabited wasteland of sand dunes and swirling dust. Abraham would leave them there in Arabia and return to Canaan alone. This, the first of many commandments God would give the prophet. And Abraham, eager to obey, gathered his small family and led them south toward Mecca.

A week’s journey and as they walked, Abraham tried to imagine how he would explain the second part of God’s commandment: That he leave Isaac and Hajar alone in the middle of Arabia and return to Canaan by himself.

After their arrival in Mecca, Abraham began pacing nervously. His wife asked him what was wrong.

“I have to leave you here,” he said, turning his gaze to the north.

“Why!?”

“I just have to go.”

Hajar grabbed Abraham’s shoulder and he turned to her.

“Why are you doing this?” she said.

The prophet sighed and peered down at the ground. He raised his eyes to meet her stare. “Because God told me to.”

Hajar nodded slowly. “Then God will not forget us,” she said. And after a long pause, “You can go.”

So Abraham said goodbye to Isaac. He hugged Hajar a long time, turned northward, and set out for Canaan, leaving his wife and only son alone in the desert.

This is how Ali explains the Old Testament story of Abraham and Issac. And it’s pretty much the way I remember it from Sunday school. The only difference is that for Muslims, like Ali, Abraham translates to Ibrahim, Isaac becomes Ismael, and God is called by His Arabic name, Allah.

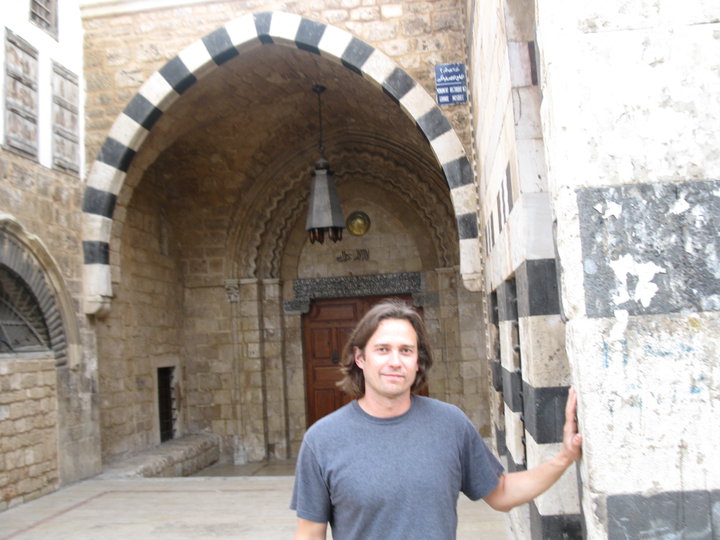

It’s my first Thanksgiving in Lebanon and this year the American holiday falls on the eve of Eid. My neighbor, Cynthia, has prepared a feast tonight. A week earlier she told me to invite any Americans from my department to join her and her Lebanese friends for dinner and a party commemorating both Thanksgiving and Eid.

Cynthia’s father, a successful engineer, took a job in the U.S. during the Lebanese Civil War, moving his family to Michigan. She spent the next twelve years in the States before returning to Beirut to attend the University of Lebanon and study Finance. Like so many in Beirut she speaks Arabic and English fluently and loves both Lebanese and American culture. Her family celebrates Ramadan, Thanksgiving, Christmas, Easter, the Lebanese Independence Day, and the Fourth of July. When I arrived tonight, Cynthia introduced me to her cousin, Ali—a tall, thin Arab man with wire-rimmed glasses. We struck up a conversation and I’ve been talking to him ever since.

“It’s a little embarrassing,” I tell him. “But I really didn’t know anything about Eid before coming here tonight. And I still know next to nothing. But I grew up Lutheran and I remember learning about Abraham and Isaac during confirmation.”

Ali smiles. “That’s really all Eid is. A celebration of the same story. Ibrihim’s obedience to Allah and Allah’s offering of a sacrificial lamb.”

In Christianity, Islam, the Druze faith, and Judaism this is where the story usually begins: Ismael tied to a stone slab, his father’s knife poised above the boy’s chest. Ibrahim, moments away from plunging the blade into his son’s heart, squeezes his eyes shut one last time, bracing himself for what he’s about to do when Allah speaks to him, telling him he doesn’t have to kill Ismael. Instead, the Lord himself, will sacrifice a lamb.

I realize Eid’s not only similar to Christian tradition, but the celebration of it’s actually a lot like Thanksgiving, which is probably why both holidays can be memorialized together so seamlessly. I talk to Ali a while longer, but I am starting to wonder about my colleagues from the university. This is their first time meeting my Lebanese friends and I realize I’ve been neglecting them, so I say goodbye to Ali and walk across the room where a cluster of my coworkers are talking with some of Cynthia’s friends. But before I can enter the discussion, we hear Cynthia’s voice from the kitchen. “Time to eat!”

In typical Lebanese fashion, it’s almost 10:00 pm as we gather for dinner. Seven years from now I’ll remember this incredible night and blog about it. Donald Trump will have just been elected president after proposing a ban on Muslims entering the U.S. and a registry for those already living in the States.

And I will be home for Thanksgiving.

In North Dakota. About to deliver firewood to the Lakota protestors of Standing Rock who, by that point, will be assaulted day and night with tear gas and firehoses from a militant group of police. Overseas, Isis will be growing more and more violent. More and more widespread. And never in my lifetime (including the first Cold War) will the world seem so close to a nuclear holocaust.

Before sitting down, Cynthia has us stand in a circle, holding hands, heads bowed, each offering our own thanks in turn.

Mohamed, who is thankful for Obama’s recent election, sees him as one of the most benevolent, intelligent, and tolerant American presidents. One who will not be so quick to make war in the Middle East. Ali is happy his mother has recovered from by-pass surgery. I am thankful for my new friends and Cynthia is glad she could host us tonight. Especially the Americans from the university. Like everyone here, she’s gone out of her way to make us feel welcome.

Later, after dinner, we’ll all countdown to Eid and when the clock strikes midnight Cynthia’s small apartment will swell with shouts and cheers—everyone hugging and raising their glasses.

But for now, we continue giving thanks.

Grateful that today Lebanon is not at war with itself or anyone else. Grateful to be making connections and celebrating new holidays. And yet, in the middle of it, explosions erupt outside and everyone flinches. A shock wave of nerves rippling around our circle, passing from one hand to the next in successive jolts of fear. It sounds like a car bomb followed by machine gun fire.

But, instead, outside Cynthia’s windows, the sky above Beirut opens up with brilliant spiders of red, blue, and purple, leaving temporary imprints on the blackness, then vanishing altogether. Only to be replaced by more fireworks as we run out to the balcony to watch.

Beirut is beautiful tonight.

The silhouette of high rises glowing orange in the strobe light of fireworks. Shadows dancing. The whole city pulsing and throbbing. The Mediterranean’s dark waters stretching out toward the Atlantic and beyond. To the East Coast of the U.S.

Somewhere out there.

Where the sun is now rising. Sending up its own fireworks of red, orange, and yellow. Sending up its light.

Toward the heavens above.